“Men of Labor, Men of Leisure: Artists in Early 18th-century England," Part 2

(continued from Part 1) For those artists who wished to move up the social hierarchy during the eighteenth century, a reputation for “polite learning” was important to cultivating their personas. A capacity for polite learning allowed them to demonstrate both social refinement and knowledge.

Take this painting by Gawen Hamilton for example. It is a group portrait which includes the painter James Thornhill and several of his friends. Thornhill was a high placed artist at the height of his fame when this painting was completed at about 1720. In 1707, he had been commissioned for the Painted Hall at Greenwich Hospital, and in 1715, he was hired to paint the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral. In 1720, the King made him Seargent-Painter, a post which led to a knighthood and election to Parliament (1722-34).

The painting shows a group of gentlemen — not men at work, but men at leisure — a group which nevertheless included practicing artists. Surrounded by symbols of learning, the overall mood of the painting is sociability and cultivation, embodying the principles of polite learning.

This painting celebrates a purchase that Thornhill made in 1717 — Poussin’s Tancred and Erminia (now in the Barber Institute of Fine Arts at the University of Birmingham). It demonstrates Thornhill’s and his friends’ taste and serves as an icon of Thornhill’s transformation from jobbing artist to collector and patron.

This point was driven home by one of Thornhill’s friends and fellow artist, Jonathan Richardson in his Essay on the Art of Criticism. Richardson described Thornhill’s taste as impeccable, comparing Poussin’s visual poetry to that of Raphael and the sculptor of the Laocoon.

In his analysis, Richardson recognized the division of physical labor and intellectual reflection — judging the labor by its ability to convey thought. Of Poussin’s labor, he wrote,

What a fine and accurate hand are absolutely necessary to the production of such a work! That two or three strokes of the pencil (for example) . . . can express a character of mind so strongly and significantly.

Of the excellence of the artistic mind, he wrote,

Let us observe for the honour of Poussin, and of the art, what a noble and comprehensive thought! What richness and force of imagination! What a fund of science and judgment.

The ability to appreciate this art not only reflected well on the mind and hand of the artist, but of the connoisseurs and collectors with the learning to recognize the quality of its technique and its literary allusions, as well as the leisure to be transported to realms of philosophical contemplation.

These tropes were not entirely new, but they did have an increased resonance among artists, connoisseurs, and collectors alike by the early 18th century. Part of this was due to the increased emphasis on travel and study on the continent. This was, after all, the dawn of the golden age of the grand tour, and knowledge of classical and Renaissance painting, sculpture, and architecture were increasingly the signs of a complete gentleman — and an artist for that matter.

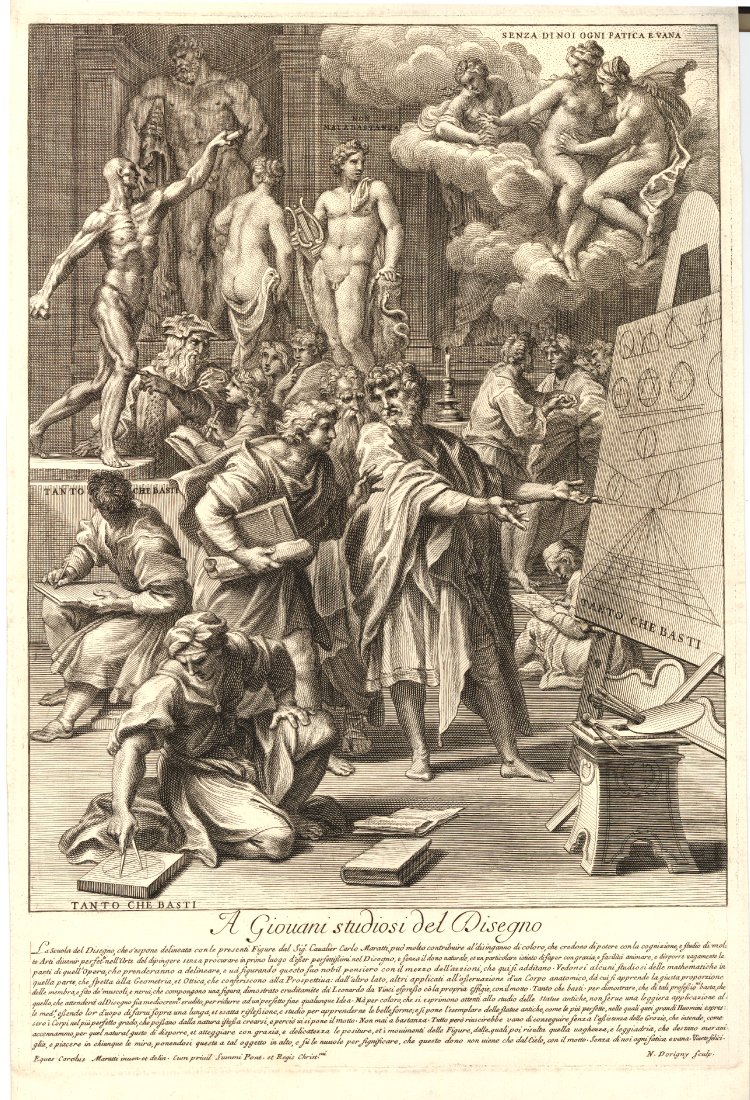

For British travelers, continental academies, which had increased in number during the 17th and 18th centuries (in part because of aristocratic patronage, which saw these institutions as valuable to bolstering reputation), set benchmarks for style and taste. Not only were the artists that they produced sought after because of their skills, but they also helped set a model of what an artist should be as is suggested by Carlo Maratti’s idealized representation of a painting academy. This ideal was more often made real in rhetoric more than in practice, but it nevertheless suggested that a complete artist had to have a command of artistic theory, philosophy, mathematics, and classical knowledge.

Variations on these themes continued in any number of works and art forms, from small engravings for artist’s manuals to full scale historical works.

In fact, the English elite, which included wealthy patrons and a small group of influential artists such as Jonathan Richardson, James Thornhill, and William Kent, valorized continental models, old masters, and artists. This led to a backlash by the 1720s.

Hogarth, Thornhill’s son-in-law, was one of the most vocal critics of the taste for foreign art. An auction ticket that he designed in 1745 had Old Masters — many of them copies — being blown by the wind and slicing through his own art.

In a similar mode, a work from 1730 portrays auctioneers and collectors as animals. The artist is losing his source of income because of the rage for Old Masters — a point driven home by the pair of pickpockets, one of whom holds a blade to his neck while the other takes his last pennies.

Still, despite being critical of the fashion for continental painters and Old Masters, these attacks often aligned with at least two elements of the discourse among elite connoisseurs: a rejection of the commercial world in which art operated as well as an effacement of the labor that went into creating a work of art.

(to be continued in Part 3)